The struggle over education has recently become one of the most significant fulcrums for our social movements’ futures. This was evident at the recent National Student Power Convergence, which welcomed over three hundred people from around the United States, as well as organizers from Quebec, Mexico, and Puerto Rico for five days in Columbus, Ohio to envision, educate, eat, entertain, and enact steps towards a better coordinated (inter!)national student movement. In a time when both pundits and activists have perversely mourned the death of a young Occupy movement, its radical education roots were content to busily blossom here. And no student power gathering would have been complete without a street march and protest outside President Barack Obama’s campaign headquarters in Columbus to decry the political system’s lack of concern for our collective futures, future which face the ugly specters of unemployment, student debt, ecological crisis, mass incarceration, and more.

The struggle over education has recently become one of the most significant fulcrums for our social movements’ futures. This was evident at the recent National Student Power Convergence, which welcomed over three hundred people from around the United States, as well as organizers from Quebec, Mexico, and Puerto Rico for five days in Columbus, Ohio to envision, educate, eat, entertain, and enact steps towards a better coordinated (inter!)national student movement. In a time when both pundits and activists have perversely mourned the death of a young Occupy movement, its radical education roots were content to busily blossom here. And no student power gathering would have been complete without a street march and protest outside President Barack Obama’s campaign headquarters in Columbus to decry the political system’s lack of concern for our collective futures, future which face the ugly specters of unemployment, student debt, ecological crisis, mass incarceration, and more.

The convergence represented nothing short of a sea-change in efforts by students and educators to create vibrant new political spaces. Participants brought a fiercely thoughtful analysis of intersectionality and anti-oppression to many discussions without apology or timidity. The environment was broadly queer and trans* positive (even though, admittedly, this wasn’t reflected in the composition of event organizers and was more a system of accountability from the participants themselves). Words wove from inquiry to argument to laughter, all in fluid motion. Twitter and livestreams mainlined people from around the world into every event (for one day, the NSPC hashtag #HereUsNow was in the top ten of global Twitter posts). Sleeping-safe spaces, caucuses, and three well-balanced meals a day were offered and considered alongside our myriad differences and ideologies. And the whole plucky crew was thrilled to see that we were making it all happen ourselves.

Reflections on the convergence

Two narratives were meant to act as the pillars for convergence. The first and regrettably prevailing one focused on middle-class students who are coming to terms with a new and intimidating set of challenges left by the generations who came before: a rapidly deteriorating planet, and the failed promises of the “bootstraps” paradigm by way of mounting student debt and dismal job opportunities. The second narrative involved the students and youth for whom a future was never promised. This included, but was certainly not limited to, young people who are trapped in the school-to-prison pipeline, the Dreamers (undocumented youth who have no access to student loans or federal financial assistance for college), and push-outs (most commonly known as “drop-outs”) who have no access to the Welfare State that middle-class students had thought they could rely on.

The strategy of movement building that sits at the nexus of these two integral narratives is what drew many to Ohio from the start. Across these two realities (and the many realities above, under, and in between), Millennials are sick and tired of being fundamentally fucked over. When these two narratives can fight alongside one another with a coherent strategy that works towards concrete gains, we will build a real youth and student power movement. The convergence demonstrated that we are already well on our way. In the words of Gloria Anzaldua in This Bridge Called Home, our movement is in the process of “erecting new bridges. We’re loosening the grip of outmoded methods and ideas in order to allow new ways of being and acting to emerge, but we’re not totally abandoning the old—we’re building on it. We’re reinforcing the foundations and support beams of the old puentes, not just giving them new paint jobs.”

To these means and end, some of the most resourceful workshops at the convergence were hosted by people who have historically not been at the center of student left gatherings. The Bronx-based Rebel Diaz Arts Collective gave a dynamic crash course on the political history of hip hop, and the necessity of organizing with music, art, and performance from the ground up in our own neighborhoods. Gabe Pendas with the Florida-based Dream Defenders shared how their foundational approach to organizing—not doing for others what they can do for themselves—created the space for students of color to lead a confident series of direct actions that began in response to Trayvon Martin’s death, and has since targeted police stations and immigration centers.

At the “Global Student Uprising” panel, alongside student activists from Mexico and Puerto Rico, a member of CLASSE named Emilie Joly shared a slew of incisive mantras for the packed room: “Start to talk about crazy ideas” (like free education for all!), i.e. don’t self-censor or dilute discussion, or we ultimately close our own doors to wider radicalizations. “A strike is only as good as you’re willing to defend it.” “Strikes suddenly create organizing time and space.” “Tuition hikes are not a dollar amount issue, but part of a larger austerity campaign.” It was clear that several months of strike organizing had heightened and distilled the CLASSE members’ political clarity in each contribution and question they offered during the convergence.

On an interpersonal note, such newly institutionalized movement practices at the convergence, such as introducing ourselves with preferred gender pronouns, would not have occurred in the student movements before us. Many students expressed that because of this practice, they felt comfortable saying that they had been questioning their own gender identity and felt safe expressing uncertainty (or finally, certainty!) in their preferred gender pronouns. We acknowledge that these kinds of anti-oppression modes are integral in ensuring that we all develop language and find words that better fit us and reflect our realities.

To be sure, while the convergence was an important step in bringing together youth from across the country, many expressed concern for reproducing the same hierarchies and tokenization in our movements that college administrators pull on our campuses. Other frustrations were raised by participants that a small group of organizers were working behind the scenes at the convergence, as opposed to instituting a more democratic decision-making process to address criticism of the program and make changes to it on the ground. As a result, autonomous participants held caucuses in order to ensure that, collectively, our different concerns were being met. In these caucuses, people came together to discuss their experiences as queer and trans* folks, people of color, vegans and vegetarians, and white anti-racist allies.

On a wider scope, another setback was due to the American Left’s historically uneven trajectories that brought many people to the convergence. In short, social movements up until the mid-Twentieth Century seldom highlighted such issues as race, gender, class, sexuality, ability, and migration in their political organizations. After a period of major social upheavals that began to address these inequalities and oppressions, government and business coordinated an assault on social movements through the late 1970s. In these conditions, identity politics arose for those who perceived that only the most immediate alliances of similarity were possible during such an embattled retreat. Throughout the 1980s, this developed into a more complex intersectional analysis that evaluated how multiple axes of oppression (and possibilities of resistance) co-existed, for which more nuanced strategies and coalitions were needed to confront them.

Today, student movement politics in the United States are largely formed out of this intersectional framework, coupled with a lack of familiarity with organizational histories and models from which to coalesce the power to determine our own futures. We’ve become familiar with critiquing our organizations as gendered, racist, and otherwise replicating dominant ideologies, but there isn’t enough work done on what new kinds of organizations we can make. What we urgently need is an emphasis on both intersectionality and organized student power. While the two largest education movements in Quebec and Chile demonstrably lack a central anti-oppression analysis within their expressions of student power, the US movement may be poised to interweave these facets quite influentially.

Building Student Power from the Ground Up

Returning to our campuses in NYC, CUNY undergraduate and graduate students are striving to act more effectively in tandem across such coalitions such as Occupy CUNY and Students United for a Free CUNY, while keeping these historically rendered strengths and weaknesses in mind. Even though resources of our highly stratified university system are concentrated at the Graduate Center, graduate students are predominantly adjunct lecturers—many of us women—who are unfunded and forced to take out loans, while being exploited and under-resourced on the job. At the same time, graduate student adjuncts and undergraduates are strategically positioned to interact with each other every day, and can be regarded as mutual, integral allies in the CUNY struggle. These partnerships can end past cycles of hostility and misunderstandings between undergraduates and graduate students, and encourage deeper collaboration across university system tiers in general.

In the spring, CUNY students discussed with Quebecois students how to approach building autonomous student movement infrastructures in the United States. Brooklyn College student organizers are starting the process of unionizing with the undergraduate student body, initially devoting our full attention to establishing assemblies in such departments as Philosophy, Political Science, Sociology, Africana Studies and Anthropology that can act as a framework to unionize the remaining departments. As we see it, the student leadership built in these initial departments can be used to leverage the university administration around increasing funding in basic student services such as printing, library hours, and subsidized textbooks. We aim to eventually run a “student power” slate for student government and take over the “company union.”

Meanwhile, on the graduate student level, members of the CUNY Graduate Center General Assembly (GC GA) have begun a similar campaign to revitalize program student associations to become more directly democratic, while retaining our general assembly space for broad discussion and creative action. An array of GC GA members have been elected to the Doctoral Students Council, and are beginning to establish an escalation strategy for highlighting issues of inequity in admissions, funding, and student/faculty/staff control of the building’s affairs. We’re strengthening political ties, while widening the scope of possibility for transforming graduate higher education so that it becomes accessible for CUNY’s entire population.

We’re also renewing a rank-and-file focus on the staid contract campaign between the PSC union and CUNY management, with plans to host mobile teach-ins outside the closed-door negotiations. Although a small minority of active grad-juncts can’t sway an entire union’s trajectory, we estimate that mounting grievances shared between students and educators can galvanize union power in both of these sectors of the CUNY system to the inspiring levels seen with the Chicago Teachers Union’s strike that began on September 10.

While taking on these ambitious projects in the city, CUNY students and educators have also begun a national conversation about building statewide student associations comparable in strength and reach to CLASSE in Quebec and ConFECH in Chile. When it comes to statewide student associations, some states are further along than others. New York Students Rising (NYSR) and the Ohio State Student Association (OSSA) are preliminary models of statewide student coalitions, but still don’t widely represent student majorities. By comparison, when Quebec’s more radical left student union, ASSÉ, wanted to call for a strike in opposition to the proposed hikes, they formed a broad-based coalition that spoke to all students in the province: CLASSÉ. In the U.S., we can use both of these organizations as potential models. So to speak, in states where we already have CLASSÉs, we need to build ASSÉs, and in states where there is no statewide association at all, we need to begin by building CLASSÉs.

These organizational models have syndicalist roots that stretch much further than our generation’s historical memory. Jasper Conner’s contemporary pamphlet on student unionism refers to Quebec’s long-standing student unions as ideal models. He outlines how, in the US, “Student Unions could replace out-of-touch Student Governments, give the boot to overpaid Administrators, and actually run the university in cooperation with other organized groups on campus.” However, in a recent Nation article, Zachary Bell also asserts that American students have mass strike potential if we build our own relevant models of meaningful student participation to meet our immediate political needs (instead of uncritically grafting models from elsewhere), while scaffolding communication structures that can enable mass mobilization.

On Free Education and Direct Action

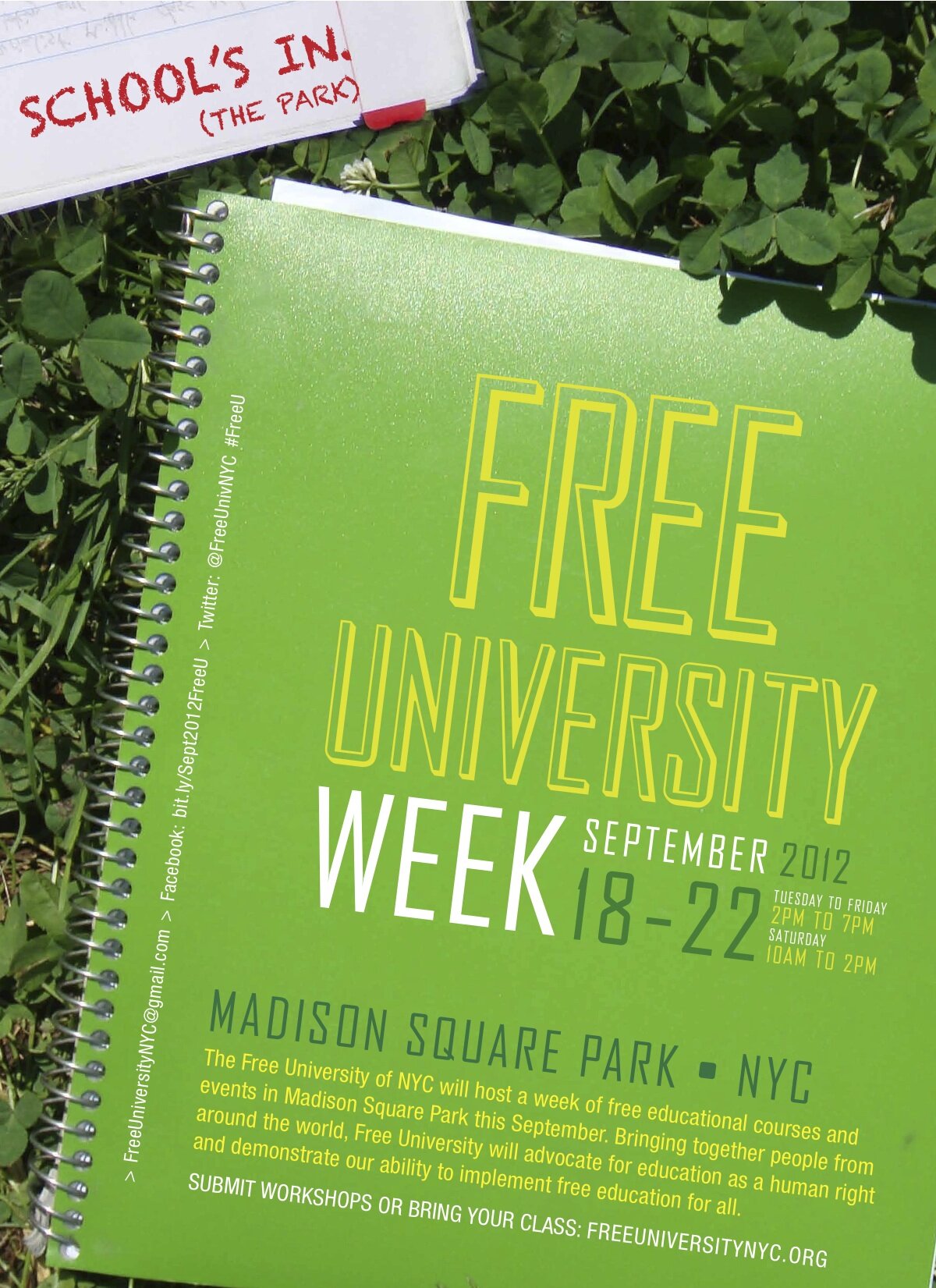

One critical city-wide effort to sustain political education is through the Free University Week, September 18-22, in New York City’s Madison Square Park. Billed as “an experiment in radical education and an attempt to create education as it ought to be,” the Free University aims to nourish the momentum of Occupy Wall Street’s September 15-17 weekend birthday bash with a space for strategizing into a whole new year worth celebrating. Building on its May Day 2012 success of over forty workshops and two thousand participants across five hours, Free U has the potential to gather—this time across several days—the dozens of intersecting movements in NYC that have needed consistent space for both direction and reflection. This educational component of Occupy’s anniversary advocates a methodically longer-term focus that eschews single-day actions for events with rolling momentum, creative and critical new models of pedagogy, and ultimately lasting radical coalitions. The Free University model is about creating educational space as an expression of informative directional action (action can’t just be direct, it has to know why and where it’s going). It’s about highlighting the necessity for serious political education in all that we do as the foundation for a mass movement.

Free University workshop series will highlight past and present models of organization and anti-oppression strategies each day that can combine lessons from the massive movements in Quebec, Chile, and elsewhere with the particular attention this country’s left has developed around intersectional issues. Each day will begin at 2:00pm with shared community agreements, followed by workshops, skills-shares, relocated classes, and performances, as well as recurring thematic areas and activities like an artists bloc, a writers bloc, poetry speak-outs, and info hubs for New York City’s various and diverse organizations. An education visioning assembly at 6pm will round out each night. Free U will welcome new and returning participants like Rebecca Solnit, Nick Mirzoeff, Ruth Gilmore, Andrew Ross, Ben Katchor, Drucilla Cornell, and the Occupy Guitarmy to join thousands of people from New York and around the world to advocate for education as a human right and demonstrate our ability to implement free education for all.

In particular, the Free University schedule will highlight a workshop series on radical student and faculty organization models from the past and present. Thursday and Friday at 4:30pm, a former member of CLASSE’s executive committee will discuss in two parts how Quebecois students coordinated a mass strike to overturn tuition hikes and oust Premier Jean Charest. A Friday, September 21, 4pm panel will feature Tina Weishaus and Jackie DiSalvo, who will share the history of Livingston College in New Jersey, a place that was directly run by students and faculty in the 1970s, and “probably the most radical college that has ever existed in the US before it was dissolved” into Rutgers. Finally, a Saturday, September 22, 11am panel will introduce how the groundwork for student union models from Quebec, Chile, Puerto Rico, and California can be precisely laid here in New York City across its public and private universities over the next few years.

More generally, we will delightedly expand the notion of what it means to have a “radical conversation.” Daily workshops and activities will focus on arts, culture, and health as powerful vehicles for community education and mobilization. Regular art-shop spaces in the park will create book shields, banners, and screen-prints. We’ll host political theater, poetry readings, learning through tangible play, sex education, and conflict resolution. For us to envision and enact fundamental social change, we need to open up a wide view of mutual engagement and growth. If not, we will be continually banished to the dustbin of lost possibilities in waging the same parochially persnickety debates with ourselves, while calling this “political action.”

Another element of the budding #HereUsNow movement is that we are excited by politics beyond the elections. Many innovative campaigns and projects will emerge this fall that represent a multiplicity of approaches to political engagement in the wake of the 2012 Presidential elections. 99Rise, an organization coming out of Occupy Los Angeles and other movement-building efforts on the West Coast, is attempting to “restore Congress” to one that is held accountable to the people and not corporate money. Their campaign is built around a non-violent organizing model passed on from the Serbian revolution and, much like the Occupy efforts of last year, thousands of people from New York to California will be targeting Wall Street bankers on September 28 via mass arrests.

Ultimately, however, coordinating days of actions alone isn’t enough to challenge the crises in higher education and government corruption. Nor is only being academically well-versed in various political frameworks. Given the scope of the crisis we are facing, students and teachers desperately need to get organized. We need to create political structures that are durable and democratic. With dialogues at the Free University and elsewhere, we can begin to envision—among many possibilities—how building a NYC Student Union over the next few years can present a long-term, sustainable view committed to developing organizational solidity and capacity at a time when student union models have demonstrated considerable power in other countries. In Quebec, the resignation of Premier Jean Charest and the new premier’s announcement that the proposed tuition hikes will be rescinded, show that victory is possible when infrastructure is in place.

Looking ahead at “American Autumn” 2.0, we will have many opportunities to patiently apply these ideas and lessons as kindling toward a slowly developing conflagration. In mid-October, Chilean student leaders Camila Vallejo and Noam Titelman will speak in NYC about their education movement’s significant new stage in contesting social power. International days of action on October 18 and November 14-21 will offer us space to express and then assess our coordinated power on campuses and in the streets.

While focusing on doing each step right, we’re also cognizant that we’re running out of time, and fast. As Nicholas Mirzoeff writes, “capitalism is choosing to drown itself rather than die.” We students and educators, on the other hand, choose to extend out a hand for people in society to save ourselves together, with inspiration from the Quebec strike, the Chilean student protests, Mexico’s #YoSoy132, and beyond. While Occupy Wall Street turns its attention towards debt as the central theme of its one year anniversary assemblies, students and educators share the forefront in constructing dynamic coalitions across the Left that can erect the new bridges we need for a sustainable future, and then get us there.

Photos: Top - Student Movement in Chile, Middle - Chicago Teacher's Strike, Sept 2012, Below - Free University, NYC