The point is to occupy our schools with clear political purpose. It’s not enough for a tiny band of adventurous students and teachers to take a school building and hoist a flag. We need to gather vast networks of resonant support if school occupations and strikes are to succeed.We can see how in Chile, Puerto Rico, California and around Europe, educational activities proliferated, rather than halted, when people effectively shut down campuses.

We’ve reached a month and a half into Occupy Wall Street—a movement catalyzing millions into decisive action around the world. For many of us, ‘occupy’ has become a verb to be sung. This rowdy crowd word, at once descriptive and prescriptive, aims to body-flip the logic of imperialism on its head. A radical people’s occupation of public space doesn’t erect checkpoints; it tears them down. Instead of usurping others’ resources, we heartily pool our own for free distribution. The call to occupy now reverberates from Oakland ports to NYC Department of Education hearings, from garish Sotheby’s art auctions to rush-hour subway ciphers. The wealthy are now hounded at public appearances, while banks begin to dance the frantic backpedal. The results are in, folks: A poor people’s movement is once again changing the course of history.

So how can we apply such electric tenacity to occupy our schools? Initially, education activists did well to look beyond the immediate horizon of campus grounds and help transform public squares--the movement’s major first act. The recent “People’s University” and “#occupyCUNY” teach-ins at Washington Square Park demonstrated, along with each OWS assembly and Open Forum, how to re-shape public places as free venues for collective education, places where each of us can actively make meaning in a range of critical discussions. With the goal of shaking prevailing school priorities inside out, these wide-open counter-classrooms have been essential. But for our second act (and just in time for winter!), we need to boomerang the “occupy” movement back to where our power was latent all along: our college environments.

Teachers and students reoccupying our schools means jettisoning many failed tenets of higher education’s current operation. Competitive individualized learning, rigid demarcation of disciplines, shallow celebration of difference, grading systems that all-too-viciously distort self-worth—these are the pedagogical tools of the 1%. Instead, let’s host at each campus OWS-style General Assemblies that welcome the surrounding community and put educationally marginalized voices at the top of the speaking list and the top of resulting activities. Let’s collaborate via write-ins to produce "People's Dissertations" about the Occupy movement’s significance, with public writing times, committees of peers and involvement across disciplines. After each dissertation is created, we can hand out P(eople)h(ave)D(dreams) certificates en masse, thus rupturing the emblems of intellectual prestige.

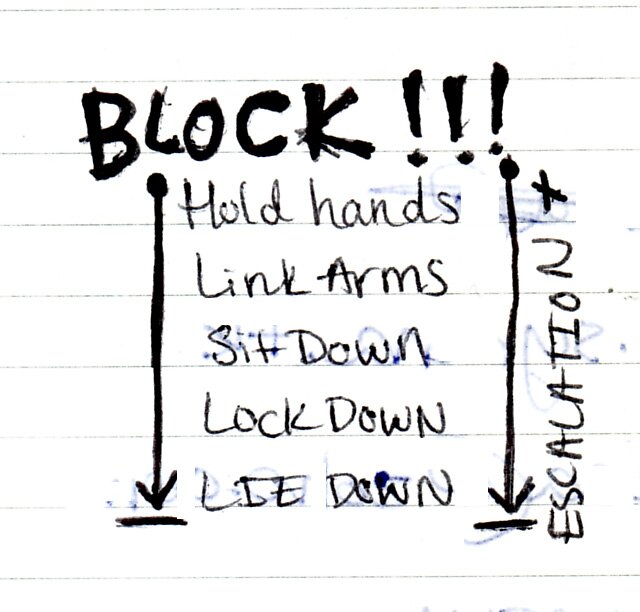

The point is to occupy our schools with clear political purpose. It’s not enough for a tiny band of adventurous students and teachers to take a school building and hoist a flag. We need to gather vast networks of resonant support if school occupations and strikes are to succeed. We need to line up a panoply of actions for the exact moment when business as usual is disrupted. We can see how in Chile, Puerto Rico, California and around Europe, educational activities proliferated, rather than halted, when people effectively shut down campuses. Labor historian Paul Johnston also suggests that “we start seeing the strike not as an ‘off button’—put down your tools, walk out, stand in front of the worksite, keep people from crossing the lines—and instead see it as an ‘on button,’” in order to galvanize a huge influx of participants into concrete action.

To dig deeper: What does it mean for us to “occupy theory”? Although some cozily ensconced radical scholars would bray otherwise, we must be clear that liberatory education is a means, not an end. Radical books that are disconnected from social action are lone flags rippling atop an otherwise unchallenged edifice. As Paulo Freire, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o and others persist, we have been inculcated in an imperialist banking model of education. The more we gain by climbing the education echelon, the more precarious becomes our resistance to it. However, the late people’s historian Howard Zinn understood the exigencies of radical scholarship: While at Spelman College, after class he and his students marched together to desegregate lunch counters. In such moments, the high walls of theory become miraculously porous; we test the learning process by leaping off the page and into lived social experience.

The relationship between ideas and currency is another target for occupation. Pierre Bourdieu calls attention to the French word “louer,” which can mean both “to praise” and “to rent.” I’m reminded of the time-worn practice of the first day of graduate seminars, in which each student goes around to share her “interests”: “I’m interested in this field, I have an interest in that methodology,” etc., etc. The word “interest” connotes somewhat of a detached, dispassionate gaze, but also contains clear economic ramifications. We borrow ideas throughout school, duly paying interest to those who own them, which thus accrues value for certain kinds of knowledge. With this inaugurating tradition of sharing one’s interests (like a banker-in-training, or otherwise like a collector of possessions), we practice the cool ownership of ideas. To liberate our education must include, then, expropriating our ideas from systemic hierarchical mis-evaluation.

Moreover, we would do well to incorporate Occupy Wall Street’s methods of discussion in our classrooms and communities. How often do we carefully strive to create consent about complex positions and concepts? We’ve been taught to theorize like starving hyenas—tearing the throat out of each other’s ideas. Instead, an interrelated educational community that listens to one another, repeating word for word if needed, can inscribe the social work of scholarship with a shared sense of critical construction. In doing so, we can attempt to break out of the last few traumatic decades’ fixation on the dis-abyss: Our social movement’s trajectory now requires re-empowerment, re-orientation, re-combobulation! We will abundantly expand the global Occupy struggle if clear alternatives to this utter failure of a system are presented, debated, attempted, assessed, re-worked, and attempted again, with each stage in the process promoting wider varied ways for people to join these spectacular efforts at social change.

Ultimately, such an expansive project will entail changing our conceptions of school altogether. Fred Moten and Stefano Harney urgently address the present underside of education, arguing, “The university contains incarceration as the product of its negligence.” Paradoxically, then, our role in transforming schools will include striving to abolish their function as the official sites of knowledge production, just as we will in connection strive to abolish prison systems that maintain colonialism by other means. To liberate schools is to liberate a society in which education codifies and contrasts people’s needs and dreams to each other’s. To this effect, the people’s class is now in session, with guaranteed free tuition and open admissions. We’re making up the syllabus as we go.